The time when the Catholic Church had three popes simultaneously is known as the Western Schism (also called the Great Schism of the West), which lasted from 1378 to 1417.

The schism was not about doctrinal issues but rather about authority and legitimacy. It began after the return of the papacy from Avignon to Rome, leading to contested papal elections and rival claimants to the papal throne.

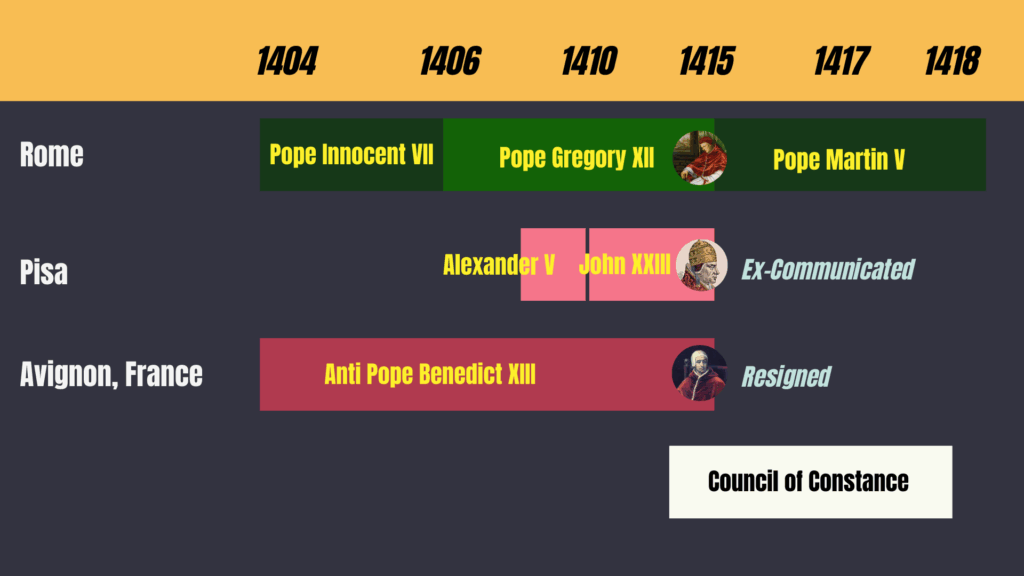

The schism was finally resolved at the Council of Constance (1414–1418), which:

- Deposed or accepted the resignations of all three claimants.

- Elected Pope Martin V in 1417, restoring unity to the Church.

The Three Popes (at the peak of the Schism):

- Pope Gregory XII (Rome)

- Antipope Benedict XIII (Avignon)

- Elected by French cardinals, he claimed to be the true pope and had the support of France, Scotland, and some parts of Spain.

- Reigned as antipope from 1394 to 1423.

- Antipope John XXIII (Pisa)

- Elected at the Council of Pisa in 1410 to try to resolve the schism, but instead created a third line of papal claimants.

- Reigned as antipope from 1410 to 1415.

Here is the timeline:

During the Western Schism, determining the valid Pope is complex because different factions supported different claimants [^1]. The schism was a period of uncertainty in the Church, with multiple individuals claiming to be the legitimate Pope [^4].

- The Beginning of the Schism: The Western Schism began after the death of Pope Gregory XI in 1378, who had moved the papacy back to Rome from Avignon [^1]. The election of his successor, Pope Urban VI, was contested, leading to the election of a rival Pope, Clement VII, who resided in Avignon [^1].

- The Lines of Claimants: This resulted in two lines of Popes: the Roman line and the Avignon line. Later, the Council of Pisa (which was not convoked by a Pope and therefore had no standing [^5]) attempted to resolve the situation in 1409 by electing Alexander V, but this only worsened the situation by creating a third line of claimants [^4] [^5].

- Uncertainty and Confusion: The existence of three claimants led to widespread uncertainty and confusion throughout the Church, with different regions and religious orders supporting different Popes [^4]. Saints, scholars, and upright individuals could be found in all three obediences [^4].

- Resolution at the Council of Constance: The Council of Constance (1414-1418) [^4], was convened to resolve the schism [^2] [^6]. The council secured the abdication of Gregory XII (of the Roman line) [^4] [^5] and deposed John XXIII (the successor to Alexander V of the Pisan line) [^4] [^5]. Benedict XIII (of the Avignon line) was cut off from the Church [^4]. The council then elected Martin V in 1417, who was recognized as the legitimate Pope by the Church as a whole [^6].

- Legitimacy: The Catholic Encyclopedia notes that it had come about that, whichever of the three claimants of the papacy was the legitimate successor of Peter, there reigned throughout the Church a universal uncertainty and an intolerable confusion [^4]. Gregory XII title is now generally held to have been the best founded [^5].

In summary, the question of who the “valid Popes” were during the Western Schism is complex due to the competing claims and the confusion of the era [^1] [^4]. The Council of Constance ultimately resolved the crisis by electing Martin V, who was then universally recognized [^5] [^6].

[^1] Catholic Encyclopedia Western Schism

[^2] Catholic Encyclopedia Council of Constance

[^3] Catholic Encyclopedia Union of Christendom

[^4] Synodality in the life and mission of the Church 34

[^5] Council of Constance (1414-1418 A.D.)